At the IUCN World Conservation Congress held in Jeju, South Korea in September 2012, a Pavilion Event 1162 showcased the culture of women divers in Jeju, and the Member’s Assembly, Motion No. 108 called for “Supporting the sustainability of Jeju haenyeo as a unique marine ecology stewardship”.

The haenyeo or women divers are a fascinating group of women who spend their lives combing the sea bed for sea products like shell fish, abalones, sea urchins, squid, octopus, small snails and seaweed. Practicing the principles of sustainable fishing by using simple tools for harvesting, these women are between the age of 15 and 86 years, and free dive into the sea without oxygen equipment, holding their breath for two to three minutes while diving to depths of 20 meters.

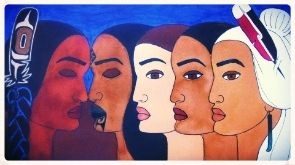

Of all the Pavilion events at the Congress, the one on the Jeju women divers intrigued me the most. As part of Jeju’s traditional and unique culture, these women have developed a female dominated profession and built up an exceptional body of knowledge on the marine environment. Through oral transmission of skills, information, safety, and a deep understanding of the sea older women teach, train and mentor younger women to become haenyeo’s.

Within this culture a woman learns how to swim at around the age of 7 years, and by the time she is an adolescent she is skilled in the art of “muljil”, the job they do in the sea. Physical strength, lung capacity, tolerance to water pressure, long periods in cold water, and sheer endurance are needed to remain alive as a free diver. And the dangers of the sea, of working alongside other marine species require extensive knowledge to be able to protect oneself in the depths of the ocean. As a haenyeo proverb illustrates; "we go to the Otherworld to earn money and return to the earthly world to save our kids”.2

These women go out to sea in groups, and in boats and sing while they row expressing their emotion to their communities through their songs. Sumbisori is a whistling sound made by the women when they surface and inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide, and rest for short periods before diving back into the sea. In the past, their diving outfits called mulot, were simple cotton garments with a cotton piece to tie their hair, and did not provide any insulation to the cold temperatures of the ocean. In the 1970’s rubber diving suites were introduced which has made diving safer and more comfortable. Older and frail women keep to the shallow waters, while the stronger one’s venture into the deep sea, risking their lives to earn a meager income to support their family.

The haenyeo population has decreased from 5,789 in 2000 to 2,500 in the last few decades, and this may be the last generation of women free divers. The only other place in the world where such free divers are found is in Japan, where women known as ama divers, and are believed to have linkages to those who migrated from Korea to Japan. The haenyeo’s are also farmers, and earn their living by growing garlic, cabbage, and other products, which they sell at local markets. Their entire livelihood is interlinked with the land and the sea.

This accumulated knowledge of nature, of the ocean, wind and tides, of harvesting on a sustainable basis, and the experience of centuries of historic tradition, is being threatened as the numbers of female diver’s falls, as the age of older diver’s increases with fewer younger women joining the profession, and as coastal pollution and the aquaculture industry leads to lower yields from the sea bed.

As in most women’s groups a strong sense of solidarity prevails among the different women who protect each other while under water, and share their experiences, and assist each other in this unusual profession. Fortunately, in Jeju at the WCC the haenyeo’s were able to exhibit there way of life, and gain support of the IUCN Members, partners, and organizations of the conservation community to preserve their unique culture, and to “endorse, and advocate the development of policies and practices which will help to protect and enhance the Haenyeo community at local regional and international levels.”3

The following story of a haenyeo illustrates the life of these women who face many dangers each time they dive, and yet they enjoy their work.

“A long time ago, I followed my grandmother while carrying a bamboo basket with wood to make a fire at the bulteok (fire pit). My taewak (flotation device) was made form a small gourd with a net sack attached. After we collected the miyeok (brown seaweed), we put it in the basket and carried it back home on our backs. We usually collected the sea weed in the spring and continued until the fall. I have never been afraid of the water even in the deep ocean. I couldn’t have become a haenyeo if I had been afraid as a child. I can dive 10 to 15 meters deep and remain underwater for about two minutes. My skills have improved over the years because I know all about the sea – where and what to catch. I have been diving for 52 years; it’s not dangerous to me. It’s enjoyable to look around. Sometime we encounter a school of dolphins, and they don’t menace us, but sometimes we feel alarmed. I love the sea and working in the water for the catch.” 4

In Jeju, at the WCC as I listened to the stories of the haenyeo’s, saw their simple diving equipment and spoke to the author of the book “Moon Tides”, I felt only admiration and respect for these women who were old enough to be my grandmothers.

“A long time ago, I followed my grandmother while carrying a bamboo basket with wood to make a fire at the bulteok (fire pit). My taewak (flotation device) was made form a small gourd with a net sack attached. After we collected the miyeok (brown seaweed), we put it in the basket and carried it back home on our backs. We usually collected the sea weed in the spring and continued until the fall. I have never been afraid of the water even in the deep ocean. I couldn’t have become a haenyeo if I had been afraid as a child. I can dive 10 to 15 meters deep and remain underwater for about two minutes. My skills have improved over the years because I know all about the sea – where and what to catch. I have been diving for 52 years; it’s not dangerous to me. It’s enjoyable to look around. Sometime we encounter a school of dolphins, and they don’t menace us, but sometimes we feel alarmed. I love the sea and working in the water for the catch.” 4

In Jeju, at the WCC as I listened to the stories of the haenyeo’s, saw their simple diving equipment and spoke to the author of the book “Moon Tides”, I felt only admiration and respect for these women who were old enough to be my grandmothers.

[1] Moon Tides, Jeju Island Grannies of the Sea, Brenda Paik Sunoo with Youngsook Han

[2] Dynamic Jeju, Wednesday, September 5, 2012 WCC Newsletter [3] M108- Supporting the sustainability of Jeju Haenyeo as a unique marine ecology stewardship[4] Moon Tides, Jeju Island Grannies of the Sea, Brenda Paik Sunoo with Youngsook Han

[2] Dynamic Jeju, Wednesday, September 5, 2012 WCC Newsletter [3] M108- Supporting the sustainability of Jeju Haenyeo as a unique marine ecology stewardship[4] Moon Tides, Jeju Island Grannies of the Sea, Brenda Paik Sunoo with Youngsook Han

Artículo leído en The International Union for Conservation of Nature

0 comentarios :

Publicar un comentario